01 December 2005

21 November 2005

.16

He got back quickly with the cooler. It was still dark out, but he had to work fast.

He took out his scalpel. Punctured neatly the skin of her abdomen—point pressing down and a little globe of blood. He cut carefully, with ease, hand sliding against her skin and surely turning the corner—a perfect right angle. He peeled back the layer of skin and there they were, like Queens, miraculously suspended over the tubes bowed and humbly waiting like willow trees. He snipped and they came with ease into his hands. Plums. He removed her ovaries. He sealed them in plastic bags, covered them in ice, closed the lid and turned one last time to her.

“Thank you for this chance,” he said to her.

He bent down. Kissed her on the forehead. Got up and wrote a note to the porter: “Signore, please forgive that I was unable to remove her as I promised. And please forgive this request, but I hope you understand that it is an act of desperation. Please take care of her. She has an orange dress with white flowers in the closet. Dress her. Brush out her hair. Braid it if you know how. And then, please, have her cremated. She looks like the kind of woman who wants to be cremated in pigtails.” He placed 500 euros on her bloody chest.

And then, he left with the cooler in his hands, in the early morning, and made his way, as the sun was rising, to the airport.

He took out his scalpel. Punctured neatly the skin of her abdomen—point pressing down and a little globe of blood. He cut carefully, with ease, hand sliding against her skin and surely turning the corner—a perfect right angle. He peeled back the layer of skin and there they were, like Queens, miraculously suspended over the tubes bowed and humbly waiting like willow trees. He snipped and they came with ease into his hands. Plums. He removed her ovaries. He sealed them in plastic bags, covered them in ice, closed the lid and turned one last time to her.

“Thank you for this chance,” he said to her.

He bent down. Kissed her on the forehead. Got up and wrote a note to the porter: “Signore, please forgive that I was unable to remove her as I promised. And please forgive this request, but I hope you understand that it is an act of desperation. Please take care of her. She has an orange dress with white flowers in the closet. Dress her. Brush out her hair. Braid it if you know how. And then, please, have her cremated. She looks like the kind of woman who wants to be cremated in pigtails.” He placed 500 euros on her bloody chest.

And then, he left with the cooler in his hands, in the early morning, and made his way, as the sun was rising, to the airport.

09 November 2005

05 November 2005

.14

The photograph was not from India. It was the tropics but not a continent. A cliff island in the Caribbean judging from the fat girl knees and the passport.

The knees were still the same, dimpled on the side, thighs sloping down and cupping the bottom of the bone, a little bowl of flesh for that vulnerable, floating cap.

How would he get her to India?

Bring those knees up to her chest, tie her up like a calf and mail her UPS ground? Would he then get a ticket for himself and meet her at the other side? Send her to a hotel room? Would he open that box and pull her out, bring her to the windowsill and say, “I brought you. Here you are, dead in India.”

Was that what she wanted?

It was hot, humid, sticky.

The back of his collar clung to the back of his neck.

He undid the top button.

Took a photograph of it. His button.

“She is born in India.”

She wanted a new beginning. She wanted a fresh start.

She saw in him an opportunity.

She had made a choice earlier that evening—to take her chances, bet that someone like him would be here, that he would collude with her—give her what she wanted. Give her a new life.

There was a reason why she had picked this night. The strip on the ovulation test kit in the trash was hot pink. She had made a choice.

The knees were still the same, dimpled on the side, thighs sloping down and cupping the bottom of the bone, a little bowl of flesh for that vulnerable, floating cap.

How would he get her to India?

Bring those knees up to her chest, tie her up like a calf and mail her UPS ground? Would he then get a ticket for himself and meet her at the other side? Send her to a hotel room? Would he open that box and pull her out, bring her to the windowsill and say, “I brought you. Here you are, dead in India.”

Was that what she wanted?

It was hot, humid, sticky.

The back of his collar clung to the back of his neck.

He undid the top button.

Took a photograph of it. His button.

“She is born in India.”

She wanted a new beginning. She wanted a fresh start.

She saw in him an opportunity.

She had made a choice earlier that evening—to take her chances, bet that someone like him would be here, that he would collude with her—give her what she wanted. Give her a new life.

There was a reason why she had picked this night. The strip on the ovulation test kit in the trash was hot pink. She had made a choice.

03 November 2005

.13

The beginning of a Romantic novel: A British child of the Orient with beautiful parents soaked in sherry. The father is drunk and has a thick black mustache. The mother is a willow-of-the-wisp. She wears perfumes and chiffon. The daughter plays with monkeys and hangs from trees barefoot in sky-blue dresses so short they barely cover her underwear. She plays with the servants, of course.

She is born in India.

So, she is wild and well bred.

Her parents never see her—just the chef, the butler and the governess. The chef and the butler wear turbans and are fond of her scampering. They make a scavenger of her—hiding coconut treats in deep pockets that she digs her little hands in. She is transported on their shoulders. Little Sahib. The governess has a Mary Poppins type jacket and skirt and lace-up shoes without all the sugar and songs. Like an Anne Sullivan—taming her unruly Helen.

She had never been to Asia. He was sure of that. She was the kind of woman who dreamed about it. Whose flirtations with British girl literature had aroused not only her curiosity of the world but had propped her burgeoning puberty. She counted herself among the Sara Crewes of the world—beloved by dark men who spoke in accents and on whose sadness her empathy could connect to a foreign place.

Where was this photograph taken? Her girl child on a slide in front of a pink house in front of a cliff—a mountainside? In that red-flower bikini. Missee Sahib was happy.

She is born in India.

So, she is wild and well bred.

Her parents never see her—just the chef, the butler and the governess. The chef and the butler wear turbans and are fond of her scampering. They make a scavenger of her—hiding coconut treats in deep pockets that she digs her little hands in. She is transported on their shoulders. Little Sahib. The governess has a Mary Poppins type jacket and skirt and lace-up shoes without all the sugar and songs. Like an Anne Sullivan—taming her unruly Helen.

She had never been to Asia. He was sure of that. She was the kind of woman who dreamed about it. Whose flirtations with British girl literature had aroused not only her curiosity of the world but had propped her burgeoning puberty. She counted herself among the Sara Crewes of the world—beloved by dark men who spoke in accents and on whose sadness her empathy could connect to a foreign place.

Where was this photograph taken? Her girl child on a slide in front of a pink house in front of a cliff—a mountainside? In that red-flower bikini. Missee Sahib was happy.

16 October 2005

.12

She had a laptop. It was on the desk by the stationery and her unmarked travel book. She hadn’t planned on going very far.

It was a Mac. A G3 and pristine. It appeared as if she had never touched the keyboard. The letters on the keys were glossy black. The white mouse pad was ungreased by the passing of her thumb. It was closed but the light showing that it was asleep was glowing. He sat at the desk. On her desktop were two files: one was the photograph of her as a five-year-old, big grin and red flower bikini. The other was a word document. He opened it.

There was one sentence on the top of the page in Baskerville, 11 point:

“She is born in India.”

It was a Mac. A G3 and pristine. It appeared as if she had never touched the keyboard. The letters on the keys were glossy black. The white mouse pad was ungreased by the passing of her thumb. It was closed but the light showing that it was asleep was glowing. He sat at the desk. On her desktop were two files: one was the photograph of her as a five-year-old, big grin and red flower bikini. The other was a word document. He opened it.

There was one sentence on the top of the page in Baskerville, 11 point:

“She is born in India.”

02 October 2005

.11

He stood over her in the bathroom.

He nudged her shin with his toe. Her head responded with a slight reverb.

He untied her left wrist.

It fell to her chest. A hollow sound. Knuckle hit the tile floor.

He dragged her by the heels to the bedroom.

There was a certain gratification to treating her body like this. It was the remainder. The leftovers. Her decoy.

He removed the gold shoes, the pink underwear. She was just a cadaver. He photographed her feet.

He stepped over her. She wasn’t there. She was a hard wall and a barrier. A moat. The alligator. He knew he was not going to win by direct force. She was Goliath and Gulliver.

He nudged her shin with his toe. Her head responded with a slight reverb.

He untied her left wrist.

It fell to her chest. A hollow sound. Knuckle hit the tile floor.

He dragged her by the heels to the bedroom.

There was a certain gratification to treating her body like this. It was the remainder. The leftovers. Her decoy.

He removed the gold shoes, the pink underwear. She was just a cadaver. He photographed her feet.

He stepped over her. She wasn’t there. She was a hard wall and a barrier. A moat. The alligator. He knew he was not going to win by direct force. She was Goliath and Gulliver.

30 September 2005

.10

She wore pearls in her ears. She was a Cancer.

The flash reproduced them as a glowing orb embedded in her ear lobe.

Her ears had probably been pierced at birth with a grandmother needle and very little blood and tears. He’d heard of these barbaric customs from the islands, and she was from the islands.

She wore the pearls like an extremity, like a benign tumor. She hardly noticed them. Like her teeth. She’d probably worn them all her life.

The forensics were moving in the hallway. He was alone with her.

The first thing he did was remove the pearls. Straightened her head to look forward at him (the fine hairs in the back still damp), and removed the pearls. He placed them in his shirt pocket.

Around her neck was a silver chain—two hearts dangling from it. A soft terra cotta color. The chain was purposeful. She’d probably put it on just after brushing her teeth and just before tying the towel around her left wrist. The way they fell on the floor, clinking in her ear, was the last sound she’d heard.

He undid the clasp and lifted her head (put his nose to her neck) and removed the necklace as well. He placed the necklace in his shirt pocket.

He would remake her.

He went to the porter, still shaken in the hallway, and gave him 300 euros and said, “Leave me alone with her. I will take care of the rest. Let no one come this way. When your manager arrives in the morning, I will be gone. The last thing you saw was the woman and the forensics.”

The porter bowed, took his euros and closed the door, “Si, Signore.”

The flash reproduced them as a glowing orb embedded in her ear lobe.

Her ears had probably been pierced at birth with a grandmother needle and very little blood and tears. He’d heard of these barbaric customs from the islands, and she was from the islands.

She wore the pearls like an extremity, like a benign tumor. She hardly noticed them. Like her teeth. She’d probably worn them all her life.

The forensics were moving in the hallway. He was alone with her.

The first thing he did was remove the pearls. Straightened her head to look forward at him (the fine hairs in the back still damp), and removed the pearls. He placed them in his shirt pocket.

Around her neck was a silver chain—two hearts dangling from it. A soft terra cotta color. The chain was purposeful. She’d probably put it on just after brushing her teeth and just before tying the towel around her left wrist. The way they fell on the floor, clinking in her ear, was the last sound she’d heard.

He undid the clasp and lifted her head (put his nose to her neck) and removed the necklace as well. He placed the necklace in his shirt pocket.

He would remake her.

He went to the porter, still shaken in the hallway, and gave him 300 euros and said, “Leave me alone with her. I will take care of the rest. Let no one come this way. When your manager arrives in the morning, I will be gone. The last thing you saw was the woman and the forensics.”

The porter bowed, took his euros and closed the door, “Si, Signore.”

21 September 2005

.9

He was beginning to understand her.

She had placed herself there for him—or someone like him. She had known that he would come, that he would be here, surveying her. And she had staged it.

She taunted him with her late girlhood—the rosebud and shoes. Presented her sophistication—the white towel. And then, she ingeniously put up the ultimate electric fence. She completely removed herself. She made herself permanently unavailable while leaving her passport open on the bed.

It was a challenge. He had to admit.

She had made it difficult. He could, after the forensics left him in charge and the porter slinked off, slip down the pink undies to her knees. He could, but she would be absent. And he wanted conquest.

He put the journal down. Crossed into the bathroom. Looked at the closed eyelids. No mascara. No shadow.

The forensics finishing up with their brushes and papers and inks.

Vacating.

She had to give in.

She had placed herself there for him—or someone like him. She had known that he would come, that he would be here, surveying her. And she had staged it.

She taunted him with her late girlhood—the rosebud and shoes. Presented her sophistication—the white towel. And then, she ingeniously put up the ultimate electric fence. She completely removed herself. She made herself permanently unavailable while leaving her passport open on the bed.

It was a challenge. He had to admit.

She had made it difficult. He could, after the forensics left him in charge and the porter slinked off, slip down the pink undies to her knees. He could, but she would be absent. And he wanted conquest.

He put the journal down. Crossed into the bathroom. Looked at the closed eyelids. No mascara. No shadow.

The forensics finishing up with their brushes and papers and inks.

Vacating.

She had to give in.

20 September 2005

.8

She had very clearly staged the whole affair. Gold and pink reflecting back up from the red-tile floor and her sunburnt skin. No one left their passport open on the bed and left everything else in the drawers and closets. She’d fully unpacked. She had been there over two weeks. The door was open. Inviting. And there was the musk and the gardenias and the brushed teeth and the shoes and the underwear, and, of course, the towel.

It was orchestrated. Down to the porter cringing in the corner and the full moon over the lake.

He was practically proud of her. It took enterprise and no shortage of guts and more than a little faith in fate. She’d practically thrown herself headlong into it. She planned it—ritualized her decision into a pattern, making her moves and her plays into intricate weavings and circlings—searching her mate and looking for a singular response. Dropping her crumbs.

It was orchestrated. Down to the porter cringing in the corner and the full moon over the lake.

He was practically proud of her. It took enterprise and no shortage of guts and more than a little faith in fate. She’d practically thrown herself headlong into it. She planned it—ritualized her decision into a pattern, making her moves and her plays into intricate weavings and circlings—searching her mate and looking for a singular response. Dropping her crumbs.

19 September 2005

.7

She was an animal.

From the bedroom door from where he stood with the journal, he could see her lower torso, pelvis and the tops of her thighs.

Despite that pill, (the half-empty pack was still on the shelf over the sink next to her wet toothbrush. She must have just brushed her teeth before tying her wrist). She could be impregnated.

He smelled her when he entered the room. Like compost. There was a biology about her. The way she had carefully left herself.

A supreme performance:

After brushing her teeth and before tying the towel, she had stripped and left on one article of clothing (if one did not count shoes and jewelry)—her underwear. White elastic grabbing her thighs and abdomen. Transparent (that was a nice touch)—her pubic hair (delta) cascading down and over her vulva under a soft screen of pink. On the elastic waist was the final touch, a rosebud.

She was a genius.

From the bedroom door from where he stood with the journal, he could see her lower torso, pelvis and the tops of her thighs.

Despite that pill, (the half-empty pack was still on the shelf over the sink next to her wet toothbrush. She must have just brushed her teeth before tying her wrist). She could be impregnated.

He smelled her when he entered the room. Like compost. There was a biology about her. The way she had carefully left herself.

A supreme performance:

After brushing her teeth and before tying the towel, she had stripped and left on one article of clothing (if one did not count shoes and jewelry)—her underwear. White elastic grabbing her thighs and abdomen. Transparent (that was a nice touch)—her pubic hair (delta) cascading down and over her vulva under a soft screen of pink. On the elastic waist was the final touch, a rosebud.

She was a genius.

29 August 2005

.6

It was not necessary for the forensics to be so thorough. He was getting impatient with the science. There was nothing to be found on her. There was not even a scent. He’d sniffed every crevice of her. She was inviolate. Her own musk pervaded even the crook of her knee. All that was left was to pump her stomach, and they would have to get her out of here for that. There was no note in her rooms. It was the first thing he had looked for when he saw that her underwear was intact. There was a journal with her ticket stubs taped to the front page: British Airways to Malpensa. There was one entry. Yesterday’s. 15.

Her handwriting had a quivering romanticism. Curves, loops and lines flowed on a slight slant upwards to the right. Taking off, gently. Occasionally, she broke off into print with words like “instincts.” The most beautifully written word on the page was: “powerful.” It was perfect script, a loop on the tail of the “p”-no break in the flow of ink and a trail at the end of the “l” that let the word into the page, taking space.

She wrote:

It is very confusing to me the person who I want to become. I understand that this is because this is a malleable thing-and not a constant. I want to be something different, or I want to be that thing in which all things are possible. This is not possible.

At this moment, I have swallowed the pill, and all my instincts are repulsed by this action. Although I understand logically that this is the way it is right now, my body knows that the time to prohibit this is over. My biology is manifesting in a powerful way. I am negating self.This is a strange feeling. Here I am-animal.

Her handwriting had a quivering romanticism. Curves, loops and lines flowed on a slight slant upwards to the right. Taking off, gently. Occasionally, she broke off into print with words like “instincts.” The most beautifully written word on the page was: “powerful.” It was perfect script, a loop on the tail of the “p”-no break in the flow of ink and a trail at the end of the “l” that let the word into the page, taking space.

She wrote:

It is very confusing to me the person who I want to become. I understand that this is because this is a malleable thing-and not a constant. I want to be something different, or I want to be that thing in which all things are possible. This is not possible.

At this moment, I have swallowed the pill, and all my instincts are repulsed by this action. Although I understand logically that this is the way it is right now, my body knows that the time to prohibit this is over. My biology is manifesting in a powerful way. I am negating self.This is a strange feeling. Here I am-animal.

09 August 2005

.5

What had she been reading?

He walked back into the bedroom. He hadn’t spent any real time there. He had swept right by the porter being interrogated, and headed for the left wrist hanging from the radiator—genteel. In the bedroom, there was a stack of seven New Yorker magazines on the dresser next to a print of an animation—a curvaceous highschool girl astride a panda. The girl was peering over her left shoulder. The panda’s eyes were slit open. The New Yorkers had not been touched. They were perfectly aligned and parallel to the top of the dresser. They were several weeks old. She’d put them there and not moved them. The picture had also not been touched. It had several days’ layer of fine dust.

On her nightstand: The Neural Control of Sleep and Waking. Jerome Siegel.

She had a white bookmark on page 63: EEG Synchrony and Behavioral Inhibition. She had put an asterisk by Figure 7.1 B and underlined in the footnote: “The line at the bottom of the figure marks the onset and offset of thalamic stimulation. The symbol S with an arrow through it signifies electrical stimulation.”

He photographed the page.

She wasn't an expert. The pages were too crisp and the binding was hardly creased. She was a dabbler. Read chapter four, “The Discovery of the Ascending Reticular Activating System” and forgot all about it. Catalogued it next to an article on the probable life-span of the cloud forest in the Cordillera de Tilaran, and thought herself well travelled. Like potholes in a field—a groundhog coming back up to tell the length of winter and forgetting. She wasn’t inhibited. She was obsessive.

The forensics were still flitting about the bruise trying to get it from another angle. Carefully trying not to touch her. She was still warm.

He walked back into the bedroom. He hadn’t spent any real time there. He had swept right by the porter being interrogated, and headed for the left wrist hanging from the radiator—genteel. In the bedroom, there was a stack of seven New Yorker magazines on the dresser next to a print of an animation—a curvaceous highschool girl astride a panda. The girl was peering over her left shoulder. The panda’s eyes were slit open. The New Yorkers had not been touched. They were perfectly aligned and parallel to the top of the dresser. They were several weeks old. She’d put them there and not moved them. The picture had also not been touched. It had several days’ layer of fine dust.

On her nightstand: The Neural Control of Sleep and Waking. Jerome Siegel.

She had a white bookmark on page 63: EEG Synchrony and Behavioral Inhibition. She had put an asterisk by Figure 7.1 B and underlined in the footnote: “The line at the bottom of the figure marks the onset and offset of thalamic stimulation. The symbol S with an arrow through it signifies electrical stimulation.”

He photographed the page.

She wasn't an expert. The pages were too crisp and the binding was hardly creased. She was a dabbler. Read chapter four, “The Discovery of the Ascending Reticular Activating System” and forgot all about it. Catalogued it next to an article on the probable life-span of the cloud forest in the Cordillera de Tilaran, and thought herself well travelled. Like potholes in a field—a groundhog coming back up to tell the length of winter and forgetting. She wasn’t inhibited. She was obsessive.

The forensics were still flitting about the bruise trying to get it from another angle. Carefully trying not to touch her. She was still warm.

08 August 2005

.4

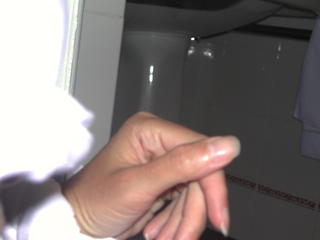

They were having trouble photographing the bruise. They asked him to come over and take a look. It was blurry.

It was not a very good camera. They couldn’t get detail in that light, at the distance which the bruise could still be seen. When they used the flash—the arm glowed white and the bruise disappeared. Without the flash, it was a blur with a slightly darkened patch. He could see it only because he knew it was there. Just an inch from her left elbow on the same arm that was tied to the radiator at the wrist. It wasn’t important. It was several days old. He’d already searched her for fresh ones. There were none. This one had been an accident. She had bumped into something—the corner of the nightstand, for instance, when she went to pick her book up in the middle of the night. She didn’t see the corner.

He imagined her rubbing it with her right hand and puckering her lips in a silent, “Ow,” at 5 in the morning. She was probably still jet-lagged.

It was not a very good camera. They couldn’t get detail in that light, at the distance which the bruise could still be seen. When they used the flash—the arm glowed white and the bruise disappeared. Without the flash, it was a blur with a slightly darkened patch. He could see it only because he knew it was there. Just an inch from her left elbow on the same arm that was tied to the radiator at the wrist. It wasn’t important. It was several days old. He’d already searched her for fresh ones. There were none. This one had been an accident. She had bumped into something—the corner of the nightstand, for instance, when she went to pick her book up in the middle of the night. She didn’t see the corner.

He imagined her rubbing it with her right hand and puckering her lips in a silent, “Ow,” at 5 in the morning. She was probably still jet-lagged.

07 August 2005

.3

They took multiple photographs of the hand. The flash popped. Her fingernails like little beacons throwing off the glint like mirrors.

The towel forced the fingers—the thumb especially—into a gesture. It seemed like she might be at lunch with her hand resting against the table or that she might be about to present a cup of tea. It was locked in place but only the wrist, slightly twisted away from her body, showed the strain.

He drifted away from the forensics to let them do their business—skin-under-nails. He already knew that they would not find anything. Maybe his thumbprint on her ankle. There was no reason to suspect that the play had been foul. The towel was a decoy.

He looked around the bathroom for a subject to keep him preoccupied. There was the bathing suit. It had already been photographed. She’d recently taken it off. It was hanging from the bar next to the toilet. It was still moist.

He smelled it.

It hadn’t been rinsed.

Still had the lake on it.

He smelled the crotch.

Still had her on it.

She was ovulating.

He bawled it up in his fist. It was damp. He was hot. It was ninety degrees outside even with the sun down—hours now. The forensics looked up at him disapprovingly.

What kind of woman owned this bikini? The plastic white rings on the hips. The bright daisies, small and naïve—the bright blue and orange of a fifteen-year-old.

Later, on her hard drive, he would find a photograph of her when she was five standing on top of a slide with a large smile and a red flower bikini with white plastic rings on the hips. Her hair was wet. She had bangs. She didn’t have bangs now. The bikini was bright blue.

He circled his finger around the inside of the plastic ring. Between her breasts there was a corresponding circle, like a large bruise. The forensics came over and bagged the top. He put the bottoms in his back pocket.

The towel forced the fingers—the thumb especially—into a gesture. It seemed like she might be at lunch with her hand resting against the table or that she might be about to present a cup of tea. It was locked in place but only the wrist, slightly twisted away from her body, showed the strain.

He drifted away from the forensics to let them do their business—skin-under-nails. He already knew that they would not find anything. Maybe his thumbprint on her ankle. There was no reason to suspect that the play had been foul. The towel was a decoy.

He looked around the bathroom for a subject to keep him preoccupied. There was the bathing suit. It had already been photographed. She’d recently taken it off. It was hanging from the bar next to the toilet. It was still moist.

He smelled it.

It hadn’t been rinsed.

Still had the lake on it.

He smelled the crotch.

Still had her on it.

She was ovulating.

He bawled it up in his fist. It was damp. He was hot. It was ninety degrees outside even with the sun down—hours now. The forensics looked up at him disapprovingly.

What kind of woman owned this bikini? The plastic white rings on the hips. The bright daisies, small and naïve—the bright blue and orange of a fifteen-year-old.

Later, on her hard drive, he would find a photograph of her when she was five standing on top of a slide with a large smile and a red flower bikini with white plastic rings on the hips. Her hair was wet. She had bangs. She didn’t have bangs now. The bikini was bright blue.

He circled his finger around the inside of the plastic ring. Between her breasts there was a corresponding circle, like a large bruise. The forensics came over and bagged the top. He put the bottoms in his back pocket.

04 August 2005

.2

He took a picture of the shoes. They had a girlish quality. They were flat, and they were gold. A woman invested in nostalgia. They were the first things he could see when he entered the room, glowing in the fluorescent lights and the red tile of the bathroom. But he was not here for the shoes. He was here because of the loosely tied towel around her left wrist.

It would have been routine otherwise, and they might not have called him in. The towel changed everything.

He had inspected the towel. White. Hotel monogram. What had she been doing? With a twist of her hand, she could have “freed” herself. It was clearly a choice, a decision, a desire maybe, even, possibly. The rest of her was on the floor but her arm hung in space, the wrist attached to the radiator by a soft white hotel towel—tied gently.

Had someone else done it and left? Or had she used her own teeth to close the knot? He touched the edge of the towel. She’d used her own teeth.

The forensics were closing in with their fine brushes against her fingertips. He noticed the perfume in her hair. Gardenias.

It would have been routine otherwise, and they might not have called him in. The towel changed everything.

He had inspected the towel. White. Hotel monogram. What had she been doing? With a twist of her hand, she could have “freed” herself. It was clearly a choice, a decision, a desire maybe, even, possibly. The rest of her was on the floor but her arm hung in space, the wrist attached to the radiator by a soft white hotel towel—tied gently.

Had someone else done it and left? Or had she used her own teeth to close the knot? He touched the edge of the towel. She’d used her own teeth.

The forensics were closing in with their fine brushes against her fingertips. He noticed the perfume in her hair. Gardenias.

02 August 2005

.1

She was wearing gold shoes and no stockings.

Her bare legs were scratchy. She had not shaved for a day or two. He swept his index finger on the lower half of her leg just above the outside of her right ankle, at the dip where lower calf slopes into bone. He should have put his gloves on.

His eyes darted back to the lime green of the inside of the shoe peaking out between the leather and her instep, the arch of her foot. He liked the arch. It was aristocratically high, and it served a function. It held up her weight.

It wasn’t holding her weight now. The right leg was bent at the knee at a ninety-degree angle, and the left was long and open—the knee pointing to the side, and the arch looking up at the sky, curving deep into her foot like a monolith.

Her bare legs were scratchy. She had not shaved for a day or two. He swept his index finger on the lower half of her leg just above the outside of her right ankle, at the dip where lower calf slopes into bone. He should have put his gloves on.

His eyes darted back to the lime green of the inside of the shoe peaking out between the leather and her instep, the arch of her foot. He liked the arch. It was aristocratically high, and it served a function. It held up her weight.

It wasn’t holding her weight now. The right leg was bent at the knee at a ninety-degree angle, and the left was long and open—the knee pointing to the side, and the arch looking up at the sky, curving deep into her foot like a monolith.